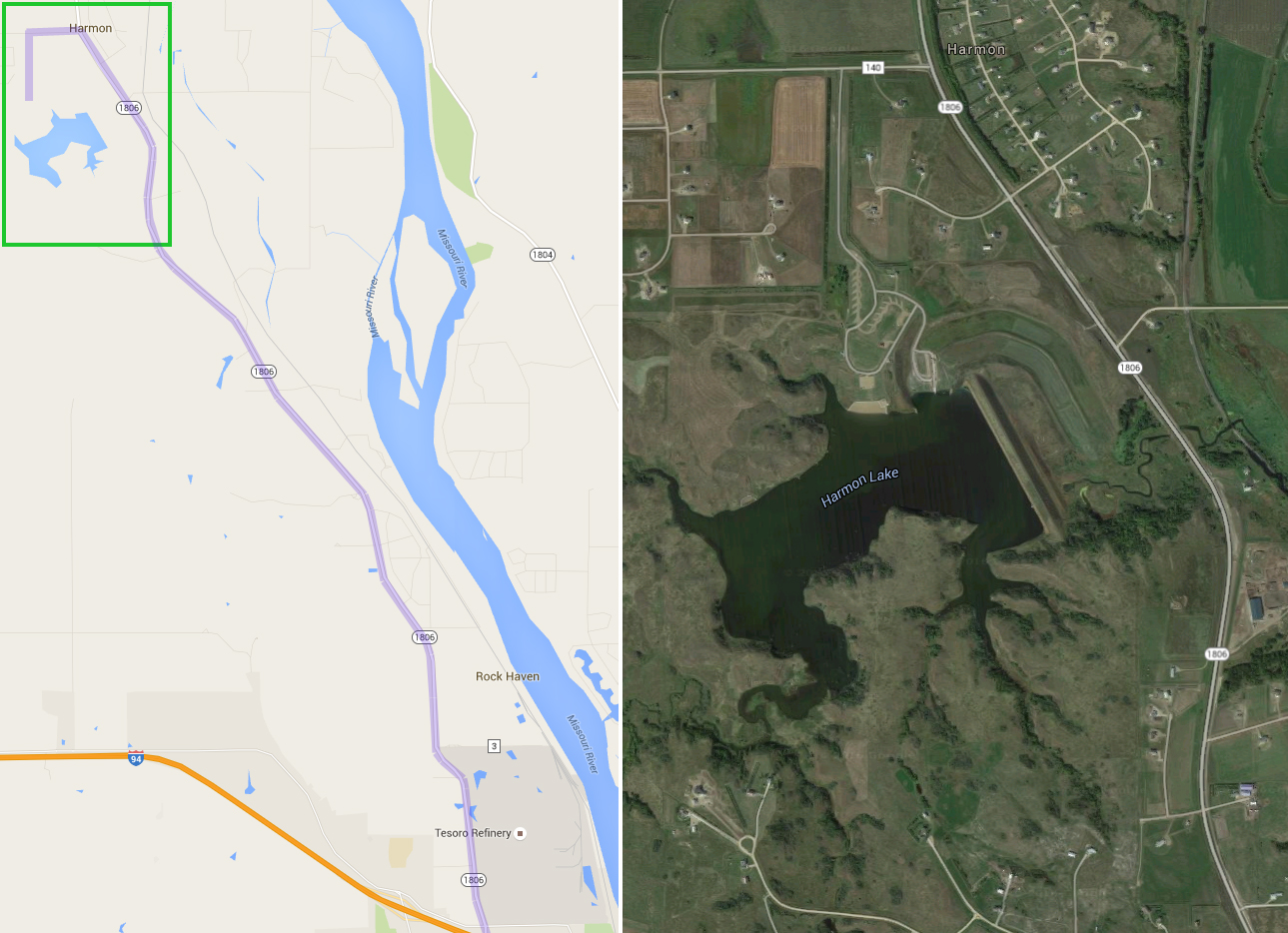

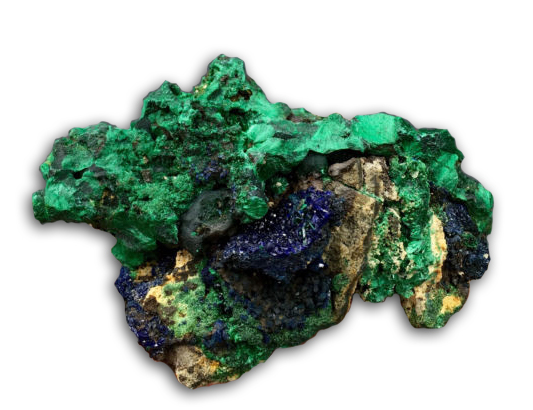

Fall of 2023 we made the trek up to Minot, ND, to visit the Nordic HostFest. While wandering around we came across a silversmith booth that specialized in “Swedish Blue”. Not knowing anything about this “stone” I took a closer look. They had raw samples for sale in a basket – and I foolishly didn’t purchase any – as well as numerous beautiful cabochons worked up in silver bezel mountings. The stone looked like a silicate, with conchoidal fracturing similar to what you might see with opal, and was streaked with varying shades of sky or stormy blues. I purchased a pendant and earrings, then later visited their website to learn more.

I highly suggest reading more about the silversmiths and stones on their page: https://www.swedishbluejewelry.com/

The trade name or gemstone name for the stone is “Swedish Blue” – especially for us English speakers that may have difficulties with Nordic dialects. However the name for the raw stone in Swedish is called “Bergslaggsten” – or stone from Bergslagen.

Beginning over 300 years ago in Sweden, the area of Bergslagen was mined heavily for iron ore. The ore was smelted in coal-fired ovens where the ore and surrounding rock was melted. When it reached a high enough temperature, a slag glaze would form at the top, which was scraped off of the metal and discarded. The slag comes in many colors, but the higher concentration of blues is what set this particular stone apart.

I was correct in my initial guess that it was high in silica – it is very glass-like, with copper giving it much of the blue-green colors. Much like volcanic glass, but from an iron foundry. The slag was discarded, and eventually grown over with local vegetation – only to be found by a Swedish goldsmith centuries later.